The Global Realignment

How Liberal Theology Became a White Man's Religion

There's a scene that plays out with increasing regularity in the grand halls of mainline Protestant denominations: Western church leaders, overwhelmingly white and educated in prestigious seminaries, gather to debate whether ancient Christian teachings still apply in our modern context. Meanwhile, in Lagos, Nairobi, and Seoul, churches overflow with believers who find such debates bewildering—not because they're unsophisticated, but because they've recognized something the Western church has forgotten.

Liberal theology, as it has developed over the past century and a half, has become fundamentally a white phenomenon. This isn't an accident of history. It's the logical outcome of a theological method that elevated European philosophical categories above the plain witness of Scripture.

The Long March of Liberal Theology

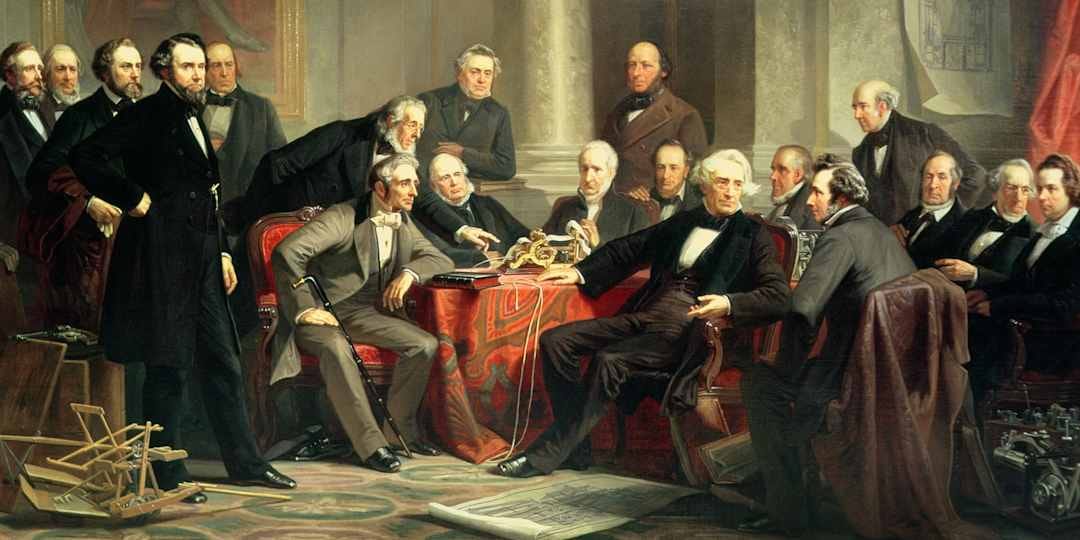

The story begins, as these stories often do, with good intentions in nineteenth-century Germany. Friedrich Schleiermacher, responding to Enlightenment critiques, attempted to ground Christian faith not in biblical authority but in religious experience and feeling. He wanted to make Christianity palatable to the cultured despisers of religion—who were, not coincidentally, educated European men like himself.

This approach spread like a slow-moving fog through European and North American seminaries. By the early twentieth century, liberal theology had established itself as the sophisticated position, the view of those who had transcended the supposedly primitive literalism of their forebears. Biblical miracles became metaphors. The resurrection became a symbol. Jesus's ethical teachings remained, but his claims to exclusive divine authority were quietly bracketed as culturally conditioned.

The malignancy of this development lay not in its intellectual rigor—liberal theologians were often brilliant—but in its fundamental posture toward Scripture. Where orthodox Christianity had always submitted human reason to divine revelation, liberal theology reversed the equation. As Paul warned the Corinthians, "the word of the cross is folly to those who are perishing, but to us who are being saved it is the power of God" (1 Corinthians 1:18). Liberal theology chose the wisdom of the age over the folly of the cross.

The American Revelation

The social and political upheaval of recent years in America has revealed something startling: the theological divide in this country runs far deeper than the cultural and philosophical rifts we endlessly discuss. America is, theologically speaking, a profoundly liberal nation—even among many who consider themselves conservative.

Consider the curious case of Doug Wilson and elements of the white nationalist movement that have attached themselves to certain corners of American Christianity. Wilson and his fellow travelers claim to champion biblical authority and traditional Christianity. Yet their views on race, their nostalgia for antebellum social structures, and their ethnic nationalism represent a radical departure from the vision Christ established.

When Jesus commissioned his disciples, he instructed them to "make disciples of all nations" (Matthew 28:19). When the early church struggled with ethnic division, Paul declared that in Christ "there is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither slave nor free, there is no male and female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus" (Galatians 3:28). The church, from its inception, was to be a radically redeemed and ethnically inclusive community—a preview of the multitude "from every nation, from all tribes and peoples and languages" standing before the throne (Revelation 7:9).

Wilson's theological method, despite his protests to the contrary, shares more in common with Schleiermacher than he would care to admit. Both subordinate scripture to cultural concerns—Schleiermacher to Enlightenment philosophy, Wilson to a romanticized vision of a white Western civilization. Both reflect the diminished view of biblical authority that characterized the academic liberalism of the nineteenth century, where the Bible became a tool to justify predetermined cultural commitments rather than the living word that judges all cultures.

This is liberal theology in conservative garb: the use of biblical language to baptize cultural preferences, the elevation of tradition over Scripture's plain teaching, the prioritization of ethnic identity over identity in Christ.

The Global Majority Speaks

While Western churches have spent decades accommodating themselves to post-Christian culture, something remarkable has happened in the Global South. The Anglican realignment through GAFCON (the Global Anglican Future Conference) and the recent split in the United Methodist Church have revealed a stunning reality: biblical Christianity's center of gravity has shifted decisively away from the white West.

These aren't minor denominational squabbles. They represent a theological earthquake. When the Global Methodist Church formally separated in 2022-2023, those who maintained traditional biblical teaching on marriage, sexuality, and scriptural authority were overwhelmingly African, Asian, and South American. The progressive United Methodist congregations that remained were concentrated in Europe and North America—and overwhelmingly white.

The same pattern holds in global Anglicanism. GAFCON, which represents the majority of practicing Anglicans worldwide, draws its strength from Nigeria, Kenya, Uganda, and across the African continent. These churches have not only maintained orthodox biblical teaching; they've grown exponentially while their liberal Western counterparts empty their pews.

Why have Christians in Africa, Asia, the Middle East, the Caribbean, and South America been able to withstand liberal theology's incursion? The answer isn't that they're theologically naive or culturally backward, as some Western progressives condescendingly suggest. Rather, they've recognized that liberal theology is a particular product of Western post-Enlightenment culture—and they've chosen Scripture over Western cultural imperialism.

When Western missionaries brought Christianity to these regions, they often brought it packaged with Western cultural assumptions. But as these churches matured, they distinguished between the gospel itself and its Western cultural wrapping. They kept the former and, increasingly, rejected the latter. They recognized that demands to revise biblical teaching on sexuality, to reimagine God in non-patriarchal terms, or to treat Scripture as culturally conditioned were not advances in understanding but capitulations to a particular cultural moment in Western history.

As the Ethiopian eunuch demonstrated in Acts 8, the gospel has always traveled beyond its cultural origins, taking root in new soil while maintaining its essential character. The Global South hasn't rejected Christianity; it's rejected the Western captivity of Christianity.

Africa at the Forefront

Across denominational lines, Africa stands at the forefront of global Christian devotion. Nigerian Anglicans, Kenyan Pentecostals, Ethiopian Orthodox, Congolese evangelicals—these communities represent not the periphery but the center of world Christianity today.

This is, remarkably, a return to an ancient pattern. During the second through fifth centuries, North Africa was Christianity's intellectual powerhouse. Tertullian, Cyprian, and Augustine—some of the greatest theological minds in church history—were African. Alexandria was a center of Christian learning with no rival in the empire. When the Council of Nicaea met in 325 A.D. to settle crucial questions about Christ's nature, African bishops played decisive roles.

The Western church has long told the story of Christianity as essentially European—a faith that moved from Jerusalem to Rome to Canterbury to Geneva. But this is historical myopia. Christianity has always been a global, multi-ethnic movement. The first gentile convert was African (Acts 8:27). The church in Antioch was ethnically diverse (Acts 13:1). When Paul needed to illustrate God's grace to the Romans, he quoted the Hebrew prophet: "How beautiful are the feet of those who preach the good news!" (Romans 10:15, citing Isaiah 52:7).

Today, as Western churches grapple with decline, Africa is once again becoming the center and seat of Christianity. This isn't merely demographic—though the numbers are striking. It's theological. African Christianity, with all its diversity and challenges, has maintained something the Western church has largely lost: confidence in Scripture's authority and clarity.

The Choice Before Us

The realignment of global Christianity presents Western believers with a choice—and it's a deeply uncomfortable one for those of us who are white and Western. We can continue to assume that our theological innovations represent progress, that our cultural moment is uniquely enlightened, that the global church simply needs time to catch up to our advanced understanding. This is the path of liberal theology, dressed in the language of inclusion and justice but rooted in cultural supremacy.

Or we can listen—truly listen—to our brothers and sisters in the Global South. We can consider the possibility that when African, Asian, and South American Christians read Jesus's words, "If you love me, you will keep my commandments" (John 14:15), they're not missing some sophisticated hermeneutical nuance. They're taking Jesus at his word.

The irony is profound: liberal theology, which claimed to liberate Christianity from cultural captivity, has instead revealed itself as the most culturally captive form of Christianity imaginable—bound to a particular moment in Western intellectual history, unable to persuade believers outside its narrow cultural context, and increasingly unable to reproduce itself even within that context.

The future of Christianity is not white. It is not Western. It is not liberal. If we have eyes to see, we'll recognize that the Spirit is moving where it has always moved: not according to our cultural preferences or intellectual fashions, but according to God's purposes. As Paul reminded the church in Rome, "God has not rejected his people whom he foreknew" (Romans 11:2). The church will endure—not because of Western Christianity's sophistication, but despite it.

The question is whether Western churches will humble themselves to learn from the global majority, or whether we will continue our long, slow march into irrelevance, congratulating ourselves on our progressive credentials while the vibrant center of Christian faith moves on without us.