The Gospel We’ve Forgotten How to Tell

Why recovering the biblical story of Jesus matters more than ever

There’s a peculiar phenomenon in American religious life: millions of people claim to believe “the gospel,” yet if you asked them to explain it clearly, you’d get wildly different answers. Some would reduce it to a formula about personal salvation. Others would expand it into a sprawling social program. Still others would speak in such coded religious language that an outsider would have no idea what they’re talking about.

This confusion matters more than we realize. The gospel—the “good news” that launched Christianity—isn’t just another religious teaching. It’s a comprehensive announcement about reality itself, about history’s turning point, and about what it means to be human. Getting it wrong doesn’t just muddle our theology; it distorts our politics, flattens our moral imagination, and leaves us grasping for meaning in all the wrong places.

The Story We’ve Lost

Here’s what we’ve forgotten: the gospel is first and foremost a “story”. Not a timeless principle, not a self-help formula, not a ticket to heaven—though it touches all these things. It’s the climactic chapter of Israel’s long story, which is itself the hinge of the human story, which is the center of creation’s story.

The narrative arc goes like this: God made a good world (Genesis 1:31), but humanity chose the path of autonomy and fragmentation (Genesis 3). We grasped at playing God, and the result was—look around—catastrophe. But God didn’t abandon the project. He called Abraham and his descendants to be a light to the nations, a people through whom “all peoples on earth will be blessed” (Genesis 12:3). Israel was meant to be humanity in microcosm, showing what a restored relationship with God looks like.

Israel’s story, though, became a tragedy of its own—exile, oppression, waiting for God to act. The prophets promised that one day, God himself would return to set things right, to defeat evil, to usher in his kingdom (Isaiah 40:9-11, 52:7). And then, in a Galilean village no one had ever heard of, it happened.

The Announcement That Changed Everything

Jesus of Nazareth appeared declaring that “the kingdom of God has come near” (Mark 1:15)—in him. Not in the distant future, not in some ethereal spiritual realm, but here, now, breaking into history. His healings weren’t just nice miracles; they were previews of a world being made whole. His meals with outcasts weren’t just provocative gestures; they were enacted parables of God’s radical inclusion. His confrontations with religious authorities weren’t just personality conflicts; they were the collision of two kingdoms.

Paul summarizes the gospel’s core with crystalline clarity: “Christ died for our sins according to the Scriptures, he was buried, he was raised on the third day according to the Scriptures, and he appeared” to witnesses (1 Corinthians 15:3-5). This is the gospel in four movements: death, burial, and resurrection.

And then came the cross—that Roman instrument of torture where the story seemed to end in failure. But here’s the stunning reversal: on that cross, Jesus took upon himself the weight of human evil, the consequences of our rebellion, the exile we deserved. As Isaiah prophesied, “he was pierced for our transgressions, he was crushed for our iniquities; the punishment that brought us peace was on him” (Isaiah 53:5). He became the place where God’s justice and mercy met, where the powers of sin and death exhausted themselves, where the old age reached its terminus. “God made him who had no sin to be sin for us, so that in him we might become the righteousness of God” (2 Corinthians 5:21).

The resurrection wasn’t just a happy ending tacked on to make us feel better. It was God’s decisive “yes” to Jesus, his vindication of everything Jesus claimed, his demonstration that death itself had been defeated. When Jesus walked out of that tomb, a new creation began. The future broke into the present. The age to come invaded the age that was passing away. As Paul writes, “if anyone is in Christ, the new creation has come: The old has gone, the new is here!” (2 Corinthians 5:17).

What This Means for Us

So what does this mean? It means that Jesus is Lord—not just “my personal savior” (though he is that), but the rightful king of the cosmos. Paul declares that God “raised Christ from the dead and seated him at his right hand in the heavenly realms, far above all rule and authority, power and dominion” (Ephesians 1:20-21). Caesar claimed that title. Presidents and prime ministers implicitly claim it today. But the resurrection announces that Jesus, not any human authority, sits at the right hand of God.

It means that we’re invited—commanded, really—to switch kingdoms. To repent, which means far more than feeling sorry for individual sins. It means a fundamental reorientation, a transfer of allegiance, a shift in how we see reality. Jesus’s first sermon was simple: “Repent and believe the good news!” (Mark 1:15). It means believing that what God did in Jesus is the most important fact in the universe and living accordingly.

And it means joining a new humanity, the church—not as an optional association for people who like religious activities, but as the advance guard of God’s new world. We become, in Paul’s language, “in Christ”—swept up into the story of the Messiah, participants in his death and resurrection, agents of his kingdom. “For we were all baptized by one Spirit so as to form one body” (1 Corinthians 12:13).

This isn’t cheap grace. It’s transformative grace. God doesn’t just forgive us and leave us as we are. He’s remaking us from the inside out, restoring the image of God that sin defaced, making us people who live now according to the rules of the age to come. “Therefore, if anyone is in Christ, the new creation has come” (2 Corinthians 5:17). Love your enemies? That’s kingdom logic (Matthew 5:44). Forgive without limit? That’s resurrection power (Matthew 18:22). Pursue justice, make peace, care for creation? Those aren’t optional extras; they’re what kingdom people do.

Why It Matters Now

In our fractured moment, when we’re tribalized by politics, isolated by technology, and anxious about the future, we need this gospel more than ever. Not a privatized spirituality that makes peace with the status quo. Not a politicized Christianity that baptizes our partisan preferences. But the full, robust, world-altering announcement that Jesus is Lord and that his kingdom is breaking in.

This gospel gives us eyes to see that no political party will save us, because only God saves. It reminds us that human flourishing isn’t found in maximizing individual autonomy or in coercive collective projects, but in living rightly before God and in communion with others. It tells us that our deepest problem isn’t lack of education or economic inequality or the wrong people in power—though all these matter—but broken relationship with our Creator. As Paul writes, “all have sinned and fall short of the glory of God” (Romans 3:23), yet “God demonstrates his own love for us in this: While we were still sinners, Christ died for us” (Romans 5:8).

And here’s the scandal: this gospel is for everyone. Not just for people who grew up in church, not just for the morally impressive, not just for a particular tribe or nation. God’s invitation goes out to all. Peter declares, “Everyone who calls on the name of the Lord will be saved” (Acts 2:21). The only requirement is that we stop pretending we can save ourselves and accept the rescue God offers in Jesus. “For it is by grace you have been saved, through faith—and this is not from yourselves, it is the gift of God—not by works, so that no one can boast” (Ephesians 2:8-9).

The Challenge Before Us

The church today faces a choice. We can continue offering a reduced gospel—either a bare transaction (say the prayer, go to heaven) or a vague moral therapy (be nice, God’s okay with you). Or we can recover the full, strange, wonderful announcement that animated the early Christians, who turned the Roman world upside down not with political power or slick marketing, but with a message about a crucified and risen Jewish Messiah.

This fuller gospel is harder to sell. It demands more. It can’t be weaponized as easily for culture war purposes. It won’t fit neatly into anyone’s ideological box. But it’s true. And truth, as unfashionable as that word has become, still matters.

The gospel isn’t finally about us—our needs, our fulfillment, our political program. It’s about God—what he’s done, what he’s doing, where his story is going. Our greatest privilege is to find our place in that story, to hear the good news and respond, to be caught up in the mission of the kingdom. As the apostles proclaimed, “Salvation is found in no one else, for there is no other name under heaven given to mankind by which we must be saved” (Acts 4:12).

That story is still unfolding. The risen Jesus still reigns. His kingdom is still advancing, often in ways we don’t expect, through means we might not choose. And his invitation still stands: repent, believe, and enter the new world that has already begun.

The question isn’t whether this gospel is believable by modern standards. The question is whether it’s true. And if it’s true, everything changes.

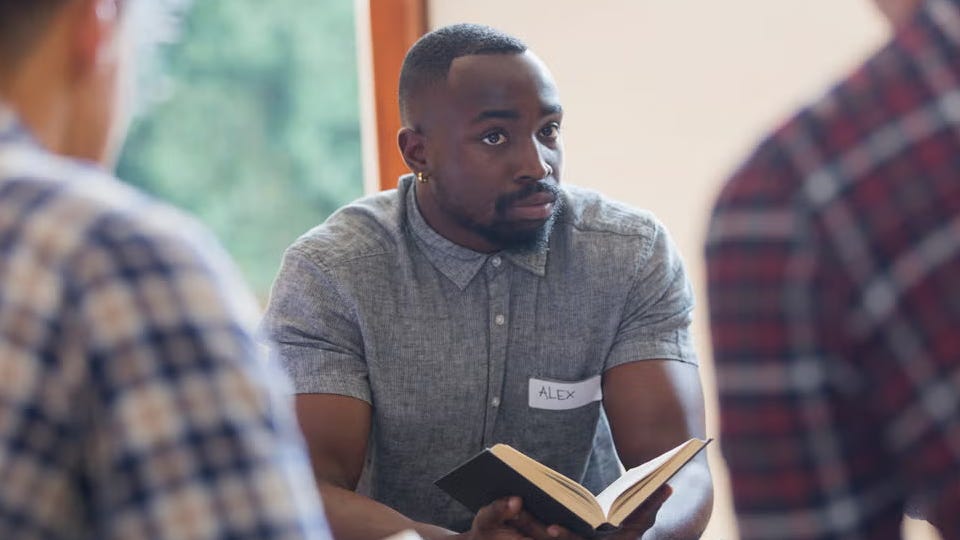

The Church is becoming theatrical in so many ways. Sermons focusing on everything but Jesus Christ and Him crucified. We must Preach “HIM” !