The Mis-education of Yolanda Adams & The Self-Disclosure of God

Why God's Chosen Language Matters More Than We Think

Gospel singer Yolanda Adams recently sparked conversation by declaring that "God is bigger than gender" and suggesting that assigning masculine pronouns to the Almighty is merely a cultural habit rather than divine truth. She's onto something important, but in her eagerness to expand our vision of God, she misses why the Bible's language matters more than she realizes.

Adams is right that God transcends human categories. The Creator who spoke galaxies into existence and knit together the human genome is not constrained by our biological limitations. As Jesus told the Samaritan woman, "God is spirit" (pneuma ho theos in Greek), and the divine nature certainly exceeds our capacity to fully comprehend or describe it. Isaiah 55:8-9 reinforces this: "For my thoughts are not your thoughts, neither are your ways my ways, declares the LORD. As the heavens are higher than the earth, so are my ways higher than your ways."

But here's where Adams's analysis becomes superficial: she treats the Bible's overwhelmingly masculine language for God as arbitrary—a mere accident of patriarchal cultures. This is where a deeper look at language, scripture, and divine self-revelation tells a more complex story.

The Grammar of the Sacred

Hebrew and Greek, the languages of the Old and New Testaments, are gendered languages. Every noun carries gender—not just people, but tables, stones, and abstract concepts. Swahili works similarly as do Arabic, French, Italian, Russian, and Spanish. In these languages, you cannot speak without choosing gender for every noun you utter.

This wasn't optional or incidental. When God revealed himself to Moses at the burning bush, he did so in Hebrew, a language that would force a grammatical choice. The divine name revealed there—YHWH (Yahweh)—takes masculine verb forms throughout scripture. In Exodus 3:14, God declares "I AM WHO I AM" (Ehyeh asher ehyeh), and immediately after, the text uses masculine pronouns: "Say this to the people of Israel: 'The LORD (YHWH), the God of your fathers... has sent me to you.'" Similarly, in Deuteronomy 6:4, the great Shema declares: "Hear, O Israel: The LORD (YHWH) our God (Elohenu), the LORD is one"—with masculine possessive forms and masculine verb agreement.

When Jesus taught his disciples to pray, he chose Aramaic and Greek words that carried gender. The masculine forms weren't imposed by later editors or translators—they're woven into the original revelation itself. The question we must ask is: Did God accommodate himself to patriarchal prejudice, or did he intentionally choose how he would be known?

A Pattern of Divine Self-Disclosure

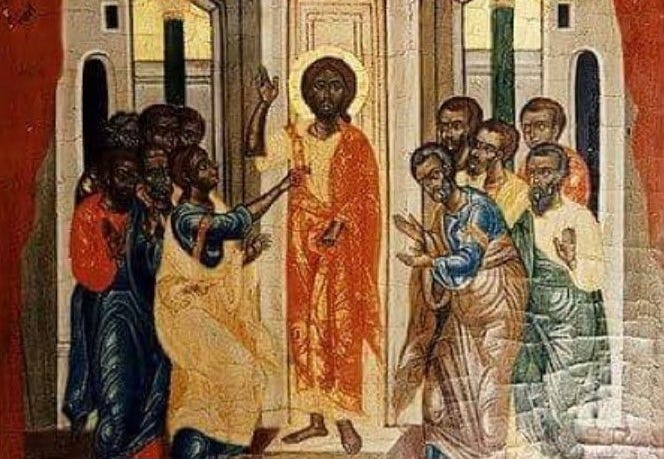

Throughout scripture, God doesn't merely tolerate masculine language—he actively embraces it in the most intimate and revelatory moments. He is Abba, Father. He is King, Lord, Bridegroom. Most significantly, when the Word became flesh, divinity took masculine form in Jesus of Nazareth.

Jesus, who upended social conventions by speaking with women, including them among his followers, and making a Samaritan woman his first evangelist, consistently called God "Father." In Matthew 6:9, he taught his disciples to pray "Pater hēmōn" (Our Father). He used this language not once or casually, but repeatedly—over 170 times in the Gospels. In John 17:1, during his high priestly prayer, Jesus looks toward heaven and says, "Pater, the hour has come; glorify your Son that the Son may glorify you." In his most anguished moment in Gethsemane, he cried out "Abba ho Patēr"—"Abba, Father" (Mark 14:36), combining the intimate Aramaic address with its Greek equivalent.

If anyone could have corrected centuries of patriarchal distortion, surely it was Jesus. Yet he doubled down on the paternal imagery. This matters because Christianity claims that Jesus is the definitive revelation of God—not just a prophet pointing toward the divine, but God made knowable. The Incarnation was itself a statement about how God chooses to be known. The masculine form wasn't incidental; it was intentional.

The Maternal Metaphors and Their Meaning

Yes, scripture contains maternal imagery for God. Isaiah 66:13 declares, "As one whom his mother comforts, so I will comfort you." In Isaiah 42:14, God says, "For a long time I have kept silent... but now, like a woman in childbirth, I cry out, I gasp and pant." These images are beautiful and true, revealing dimensions of God's character that masculine imagery alone cannot capture—tenderness, nurture, fierce protective love.

Jesus himself employs such imagery in Matthew 23:37: "O Jerusalem, Jerusalem... How often I have longed to gather your children together, as a hen (ornis) gathers her chicks under her wings." The metaphor is striking and poignant. Wisdom literature personifies divine Wisdom (Chokmah in Hebrew, Sophia in Greek) in feminine terms throughout Proverbs 8.

But—and this is crucial—these are always metaphors and similes, introduced with "like" or "as." God is ‘like’ a mother. God ‘acts as’ a mother hen. The text signals these as poetic comparisons, expanding our understanding while never replacing the primary language of Father, Lord, King. When the Psalmist writes in Psalm 103:13, "As a father (ab) has compassion on his children, so the LORD (YHWH) has compassion on those who fear him," the father image functions as identity, not mere comparison.

Scripture uses feminine imagery to illuminate certain aspects of God's character, but reserves masculine language for his identity and relationship with his people. The Hebrew word for God's compassion, rachamim, derives from rechem (womb), yet this maternal-rooted mercy is consistently attributed to the Father.

The Danger of Linguistic Imperialism

Adams's approach, however well-intentioned, reflects a particularly modern and liberal Western impulse: to flatten all distinctions in the name of inclusivity, to treat traditional forms as arbitrary constraints rather than meaningful revelations. This is the mindset that assumes our contemporary sensibilities are wiser than the accumulated wisdom of revelation itself.

There's an unexamined arrogance in the suggestion that God's self-disclosure in scripture was merely culturally conditioned—that we now know better than the prophets, apostles, and Jesus himself how God should be addressed. When Paul writes in Romans 8:15, "You did not receive a spirit that makes you a slave again to fear, but you received the Spirit of sonship (huiothesias). And by him we cry, ‘Abba’, Father (Pater)," he's describing the very heart of Christian identity. To dismiss this as cultural conditioning is to gut the text of its meaning.

In Galatians 4:6, Paul reinforces this: "Because you are sons, God sent the Spirit of his Son into our hearts, the Spirit who calls out, ‘Abba’ Father (Pater)." The consistent use of Pater and Abba across the New Testament isn't accidental—it's the grammar of relationship that God himself has established. It treats divine revelation as a rough draft awaiting our editorial improvements.

Moreover, it misunderstands how language shapes reality rather than merely describing it. The biblical narrative isn't just telling us facts about a distant deity; it's inviting us into relationship. A father is different from a mother—not better or worse, but different in role, in relationship, in the way love is expressed and authority is wielded. When God reveals himself as Father, he's telling us something about the nature of our relationship with him and his relationship with the Son.

The Real Transcendence

Here's the paradox Adams misses: God's transcendence isn't best honored by vague, gender-neutral abstractions. It's revealed precisely through his willingness to make himself knowable in specific, concrete, even scandalously particular ways.

God didn't remain a distant "It" or an amorphous "Higher Power." He bound himself to a specific people, spoke through particular prophets, and ultimately became a specific man in a specific time and place. John 1:14 declares, "The Word (ho Logos—masculine) became flesh (sarx egeneto) and dwelt among us." Not an idea, not a principle, but flesh—human, particular, and in this case, male.

In Colossians 1:15, Paul writes, "He (autos—masculine pronoun) is the image (eikōn) of the invisible God, the firstborn over all creation." This isn't God becoming small—it's God stooping to meet us where we are, in the only way finite creatures can know infinite reality: through particularity.

The masculine language for God isn't a limitation imposed on him; it's a gift he's given us. It tells us that this God is personal, relational, purposeful—that he has chosen to be known in a certain way, and that choice itself is revelatory.

A Humble Posture

Adams wants to honor God's vastness by loosening the constraints of language. But in doing so, she risks losing the very specificity that makes relationship possible. You cannot love an abstraction. You cannot pray to a principle. You cannot trust a cosmic "It."

The better path forward isn't to dismiss biblical language as culturally conditioned artifact, but to ask what God might be teaching us through the language he chose. Why Father and not Mother as the primary name? Why masculine forms in the Incarnation? What does this tell us about God's nature, his relationship with creation, the shape of divine love?

These questions require humility—the humility to receive revelation rather than edit it, to be taught rather than to correct. They also require us to distinguish between God's essential nature (which does transcend gender) and the specific ways he has chosen to reveal himself (which include deliberate masculine language).

Yolanda Adams is right that God is bigger than our categories. But God is also more specific, more intentional, more purposeful in his self-disclosure than her comments suggest. The language of Father isn't a cage constraining God—it's a door he's opened for us, inviting us into the relationship he's chosen to establish.

Perhaps the real question isn't whether God is "bigger than gender," but whether we're humble enough to let God tell us who he is, rather than insisting he conform to our sensibilities. That kind of humility—receiving rather than revising, listening rather than lecturing—might be the truest form of worship we can offer the One who is indeed far greater than we can ask or imagine.